| contents | Laws of Form | about | arithmetic play area | algebra play area

|

new edition (February 2013): summary of changes

| YouTube video to get you started in the

algebra play area | Robbins

conjecture

| (April 2016) First Order Logic/Predicate

Calculus using Laws of Form

| NEW!! (April 2025) article: Pervasive Simplicity: Investigations of the Primary Algebra of Laws of Form

| Simplification Algorithm

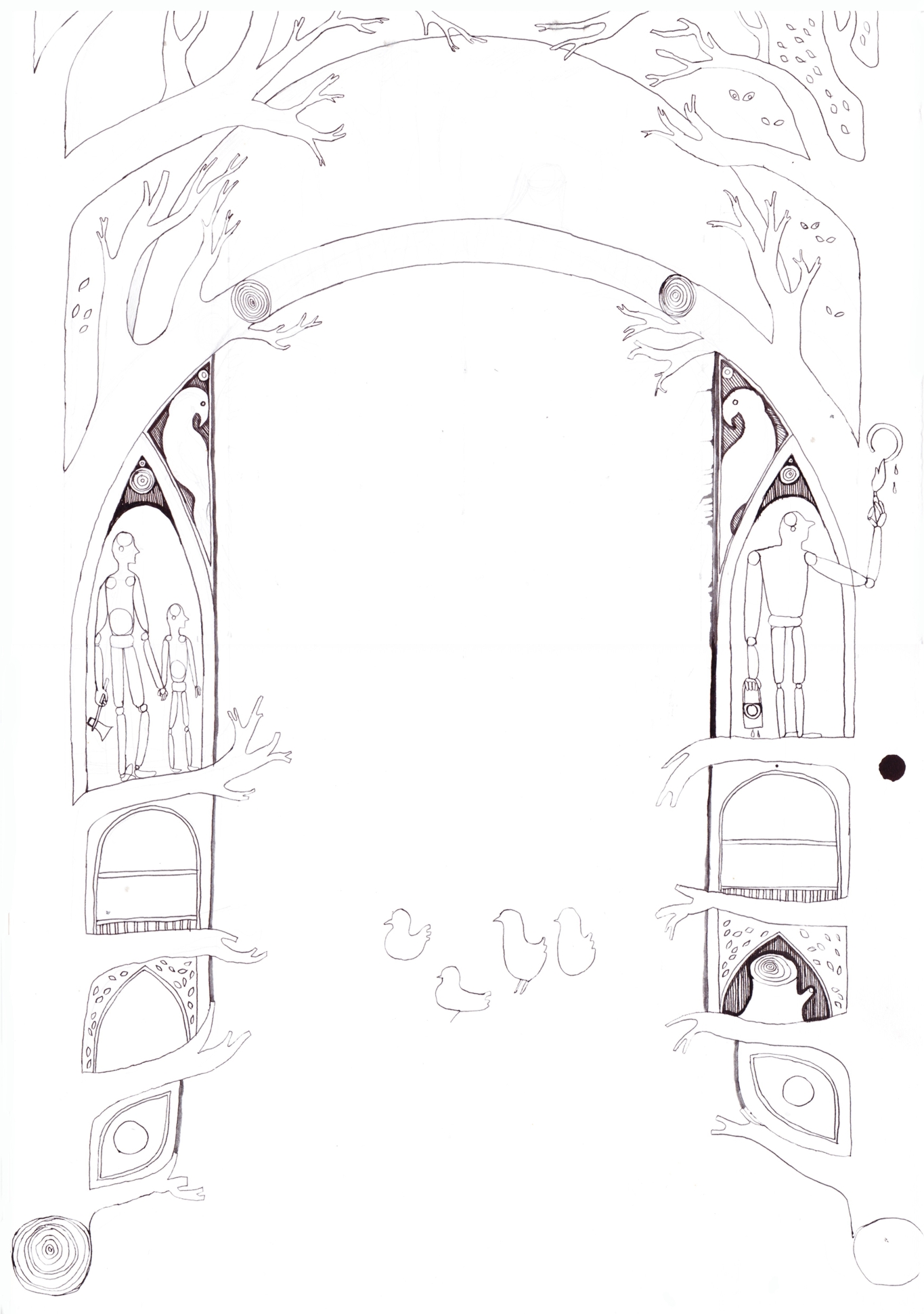

Once upon a time, there was a poor woodcutter who lived with his family in the middle of a wood.

... He took his orders from a mysterious forester who lived outside the wood, and never showed his face to the woodcutter. Instead, he would come in the middle of the night - or at any rate at some such time that neither the woodcutter, nor any member of his family, ever saw him - and mark the trees that he wanted cut down.

The mark used by the forester was a circle, made with red paint, daubed on the bark of the doomed tree. It looked like this:

The woodcutter would wander round the wood during the daylight hours, and whenever he came across a marked tree he would fell it. For each tree that he felled, he would receive a bushel of grain, delivered mysteriously during the night. If by any chance he felled an unmarked tree, or missed one of the marked trees, he would find that one of his flock of hens had been removed. This was the sign that he had made a mistake, and the next day he would look round the wood extra carefully, to discover where he had gone wrong. It was always a bitter blow to lose a chicken; but over the years he found that the forester was invariably fair - he played by the rules, even if they were a bit harsh.

Sometimes, the woodcutter would find two marks on a tree, either side by side, or, more usually, on the front and the back of a tree-trunk. In such a case, he assumed that the forester had forgotten that he'd already marked a tree, but that it was at any rate still the forester's will that the tree be felled, and the woodcutter acted accordingly. This never led to the loss of any chickens, so the woodcutter learnt that it was a rule of the game that two marks on a tree - or even more than two - meant the same as one: a marked tree was none the less marked for having more than one mark on it.

Sometimes, as well, the forester would change his mind about a tree - at least, that was what the woodcutter finally managed to work out, after losing quite a few chickens. The forester had his own particular way of unmarking a tree that had already been marked, namely, he would draw a second circle, not beside the first, but inside the first.

Apparently, the second mark had the effect of negating the original mark. If the forester changed his mind again (so he wanted the tree felled, after all), he would just make a third mark beside the cancelled first one, thus:

Sometimes, as if in playful spirit, he would accomplish the same end in a different way. He would paint a third mark inside the second one. The woodcutter (who was actually quite a clever man - and on top of that, he was often accompanied by his 10-year old son, as he went round the woods) thought that if he squinted very hard at it he could just see a sort of logic in this: it seemed that the third mark cancelled the second one, meaning that the interior of the first mark was not marked after all, so that it was after all a good effective mark, signifying that the tree had to be felled.

Very occasionally, the forester changed his mind about a tree that already had two marks on it. If the two marks were on opposite sides of the trunk, he would cancel the two marks individually, 'marking' the interior of each mark with another mark, thus:

But if the two marks were side by side, he could save paint (or time, at least) by cancelling them both with one stroke: he would surround both circles by a third one, thus:

It seemed that this pattern of three circles amounted to 'no mark' just as much as one circle inside another. In a way, thought the woodcutter's son, it followed the same logic that worked in the case of the three nested marks. The interior of the outermost circle was 'marked' just as much by two circles, side by side, as by a single circle: therefore, the outermost circle was no mark, and the tree must be spared.

In the course of time, ever more complex patterns of circles appeared on the trees. It was hard to believe that the forester was changing his mind so often, and forgetting, so often, about marks that he had already made. It seemed, rather, that the forester must enjoy making these complex signs for their own sake. It was as if he had discovered a new art-form. But the signs never quite left their practical purpose behind. It seemed that even the most complicated sign always had an unambiguous interpretation. It always said either 'fell this tree' or 'leave it alone'.

The woodcutter (getting quite old by now) used to say, gloomily, 'I'm sure that one of these days the forester will come up with a sign that we will be unable to interpret, or that we can interpret both ways. And once he finds out how to do that, that will be the end of our chickens.' But the son said 'Nonsense, father. I have worked out a method of interpreting any sign whatsoever. It works every time, it can't go wrong!'. The woodcutter didn't feel quite convinced, but there was no stopping the boy explaining what he had worked out.

continue to the next page...

but before

you do so, have a go in the play area, below. Just get clicking with that mouse!